China’s decision to embed Russia inside its planning for a Taiwan contingency is formally packaged as a limited procurement and training arrangement. On paper, it concerns armored vehicles, artillery, support systems and the specialist instruction of a single airborne battalion in delivering that equipment from the air. In contractual terms it looks like a narrow, almost routine, extension of long-standing military–technical exchanges.

Seen from the vantage point of Taipei, Tokyo, Brussels and Washington, it functions quite differently. It operates as a connecting joint between two crises that have previously been treated as separate theaters and separate temporalities: a prospective war over Taiwan in the Western Pacific and a renewed confrontation with NATO along Europe’s eastern and northern arcs. What appears as a battalion-level program is better understood as the first visible layer of a cross-theater deterrence architecture that Beijing and Moscow are constructing incrementally.

The structural character of this relationship is not that of a formal alliance. There is no mutual defense treaty, no integrated command, no shared operational planning staff. Instead, what is emerging is a layered partnership in which technological transfers, doctrinal borrowing and limited operational coordination accumulate across time. Each crisis is kept formally compartmentalized, yet the underlying military interactions and political narratives increasingly interlock. It is this process of interlocking, rather than the absolute scale of any single program, that now matters for force planners.

For much of the past decade, bilateral military activity could be treated as signaling rather than as rehearsal. Joint naval exercises in the northern Pacific, combined bomber patrols through the East China Sea, and episodic activity near Alaska or in Arctic approaches were calibrated to register opposition to a US-led security order without anchoring that opposition in specific campaign scenarios. They were demonstrations of convergence rather than components of an integrated operational design.

The decision to develop an air-manoeuvre battalion around Russian hardware and methods marks a shift from generic signaling to scenario-conditioned preparation. Public reporting and leaked documentation indicate that Moscow has agreed to supply airborne-capable armored vehicles, assault guns and associated systems, and to train a dedicated unit of the People’s Liberation Army in high-risk air assault tactics. The objective is to deliver armor and special forces onto open and suitably firm terrain in the vicinity of critical infrastructure, including airfields and ports within reach of Taiwan.

This is an inherently specific capability. It is optimised for the opening phase of a high-intensity Taiwan contingency in which an attacker seeks to degrade command and control, disrupt mobilization cycles and seize key nodes before the defender has fully dispersed and hardened its posture. Conceptually and practically, it draws on Russia’s experience in Ukraine. The early attempt to seize Hostomel airfield and other critical points did not generate decisive operational advantage, in part because of misreading of Ukrainian air defenses, underestimation of ground resistance and deficiencies in joint coordination. It did, however, produce an unusually dense body of operational experience in the planning, execution and recovery from airborne assaults under modern fire conditions. The transfer of this experience to the PLA, alongside equipment, allows Beijing to compress the trial-and-error cycle that would otherwise be required to adapt legacy airborne doctrine to contemporary air defense, electronic warfare and precision fires environments.

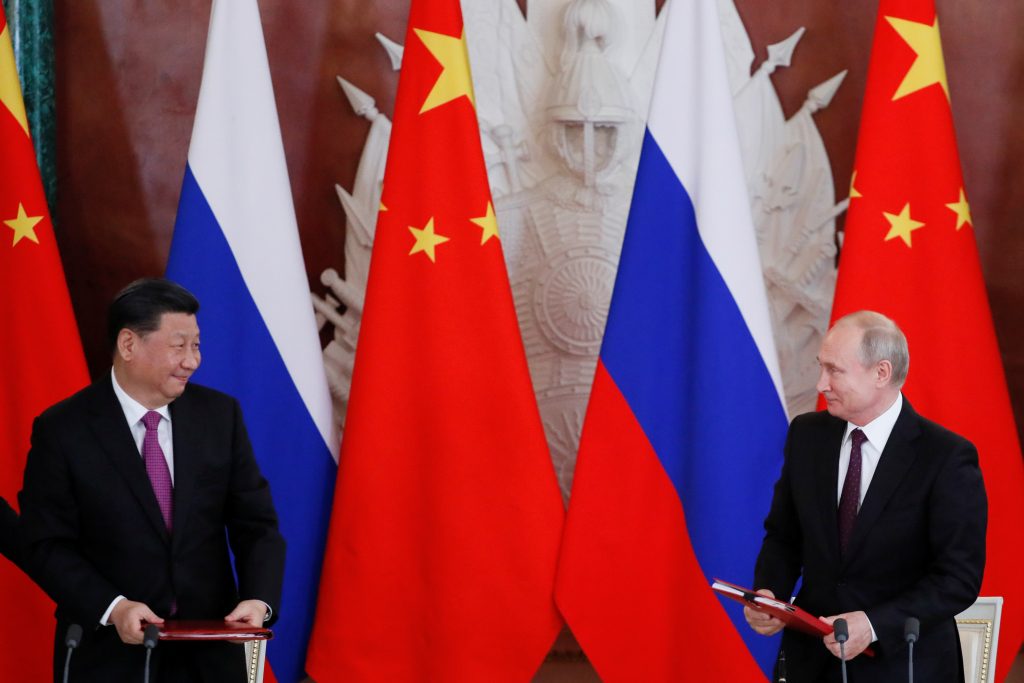

The political framing for this cooperation is supplied by the expanding shared vocabulary of sovereignty, territorial integrity and resistance to external encirclement that now structures high-level statements in both capitals. Within that discourse, Taiwan is folded into the same conceptual category as the Ukrainian front. Both are presented as theaters where external interference and alliance enlargement allegedly threaten regime security and territorial coherence. The Taiwan question is no longer treated solely as a residual issue of civil war and national unification but as one axis of a wider contest over international hierarchy and intervention.

For Beijing, airborne insertion is an additional vector of coercion rather than a substitute for amphibious lift. The material geography of the Taiwan Strait remains the central constraint. The distance is too great for low-risk helicopter shuttle operations and too constrained to permit large naval formations a generous maneuver box under fire. Any serious attempt to seize and hold the island would still require the movement of substantial ground forces and heavy equipment across a maritime choke point saturated with long-range sensors, anti-ship missiles, submarines and layered air defenses.

Air-dropped armor does not resolve the fundamental problem of mass and sustainment. It cannot deliver and support the multiple combined-arms brigades that would be needed for prolonged urban combat across Taiwan’s major population centers. What it offers is tempo, positional advantage and cognitive shock. A well trained airborne battalion, equipped with light armor and able to land in usable strength behind defensive lines, could attempt to seize a major international airport, a port complex, an energy hub or a national command node in the first hours of a campaign. If successful, such a seizure could disrupt mobilization, fracture the defender’s operational scheme and force the political leadership to manage crises across several axes simultaneously.

Russian operational practice in Ukraine demonstrates both the utility and the exposure of this approach. Poorly integrated assaults produce isolated pockets of elite troops that become attrition sinks. Well integrated assaults, aligned with long-range fires and information operations, can create temporary ruptures in defensive coherence and force suboptimal redeployments. The key determinant is not hardware but the integration of airborne operations into a broader system of joint fires, electronic attack and information warfare.

Russian assistance is therefore particularly significant in relation to the hardest elements of modern air-manoeuvre. Contemporary airborne operations must transit through dense, multi-layered air defense architectures, operate in heavily contested electromagnetic space and survive under pervasive surveillance by unmanned systems. Ukraine has become a practical seminar in the interaction between drones, counter-drone systems, electronic warfare, cruise and ballistic missiles, decoys and air defense radars. Russian officers who have had to adapt their tactics and command-and-control processes under these conditions now form the core of the training value for the PLA. What China acquires is not an assured capability for a single decisive stroke but a broadened menu of options: decapitation raids against political or military leadership, opportunistic seizures of offshore islands, diversionary drops intended to pull Taiwanese maneuver units away from main landing axes, or precision raids on specific strategic facilities.

The significance of this for Europe lies less in any direct application of the battalion itself and more in what it reveals about the evolving logic of the bilateral partnership. The first linkage to Europe is arithmetic. A high-intensity Taiwan contingency would absorb a very large share of US carrier strike groups, attack submarines, long-range bombers, air and missile defense systems and enablers such as tankers and ISR platforms. It would also demand a significant proportion of the US logistics, cyber and space support architecture. Even current, comparatively modest, shifts in US focus toward the Indo-Pacific have already translated into increased expectations that European allies assume larger responsibility for deterrence and defense along NATO’s eastern flank and for sustaining Ukraine’s war effort. In a full-scale Taiwan conflict, that expectation hardens into structural necessity.

The second linkage is operational and concerns the distribution of allied forces along the first and second island chains and across the North Pacific. Chinese air and naval activity around Japan, including joint air and maritime patrols with Russian assets in the Sea of Japan and East China Sea, has become regularized rather than exceptional. Naval patrol tracks now extend deeper into the central and northern Pacific. Russian submarines appear more frequently near Japanese islands that sit astride approaches to Taiwan, including those at the southern end of the archipelago. Chinese carriers have begun to operate farther east with greater routine, testing detection, tracking and response cycles of US and allied forces. In a Taiwan contingency, this pattern allows Moscow to assume a complementary role in constraining Japanese and US maneuver space in the north while Beijing concentrates combat power against Taiwan itself.

The third linkage operates through what might be called the logistics and infrastructure layer of Euro–Atlantic security. Chinese capital and operators are embedded in a range of European port facilities and associated logistics platforms. Russian naval modernization, combined with an increased tempo of activity in the Arctic and North Atlantic, has sharpened NATO concerns about sea lines of communication, undersea infrastructure and the security of reinforcement routes. In the context of a Taiwan crisis, Beijing would have rational incentives to leverage any available logistics footholds, data access or political influence in Europe to complicate alliance efforts to move forces, protect critical infrastructure and maintain maritime situational awareness. Even indirect or deniable measures at this layer could add cumulative strain to an alliance simultaneously managing a protracted war in Ukraine and heightened Russian pressure on its flanks.

These developments are gradually being internalized in allied strategy. Public arguments by senior NATO officials that Russia and China must be treated as a single strategic problem in planning terms, despite the absence of a formal alliance between them, express this shift. The implication is clear. A war over Taiwan cannot be conceptualized as a remote Asian contingency with limited implications for European security. It becomes a scenario in which Russia might seek to exploit the diversion of US attention and high-end platforms to test or destabilize NATO’s northern or eastern periphery, or at a minimum to intensify coercive activity in domains that fall below the threshold of direct armed conflict.

For Moscow, cooperating with China on Taiwan-related capabilities is a multiplier on its own confrontation with the West rather than a diversion from it. Arms sales and training contracts generate hard currency, sustain segments of its defense–industrial base and maintain access to foreign components and know-how despite sanctions. They also embed Russian expertise in Chinese force development in ways that reinforce long-term dependence and political alignment.

At the narrative level, joint military–technical projects help to fix a shared interpretation of the strategic environment in which the United States and its allies are treated as the primary sources of instability in both Ukraine and the Taiwan Strait. As the two capitals reiterate a common vocabulary of opposition to hegemonism and external interference, Beijing’s room to hedge between Moscow and Western capitals narrows. For the Kremlin, this constriction of Chinese hedging space is itself a strategic gain.

The most consequential effect, however, lies in temporal coupling. By helping China build the capacity to threaten Taiwan more credibly, Russia increases the probability that any major Pacific crisis will coincide with an elevated level of confrontation in Europe. From Moscow’s standpoint, an American leadership forced to triage between theaters becomes more constrained. Intelligence coverage of the Black Sea, the Baltic and the Arctic can be diluted. Reinforcement timelines for NATO’s front-line states can be stretched. Washington’s tolerance for escalation risk in Ukraine can be reduced if decision makers fear simultaneous crises in both Europe and the Western Pacific.

This does not automatically translate into a Russian decision to open a second conventional front in coordination with China. The ongoing war in Ukraine, personnel constraints, domestic political considerations and the risks of direct confrontation with NATO impose real limits. What it does enable is a spectrum of coercive actions short of overt war: intensified cyber operations against critical infrastructure, manipulation of energy supplies, aggressive naval and air maneuvers in the High North and Baltic region, calibrated nuclear signaling, or destabilizing activities in vulnerable neighboring states. Each of these options, if activated while the United States is heavily committed in the Pacific, would force NATO governments to reallocate attention and resources.

Western debate often oscillates between two inaccurate simplifications. One treats China and Russia as a fused bloc with fully aligned interests and integrated capabilities. The other treats their joint activity as superficial theater. Both miss the evolving reality. Beijing remains cautious about direct entanglement in the European war, avoids overt transfers of large-scale lethal aid that might trigger sweeping secondary sanctions and continues to value access to advanced technology and markets in Europe. Moscow, for its part, is wary of excessive dependence on China and retains its own reasons to keep limited channels open with selected European states.

Operationally, joint patrols and exercises are still modest in scale relative to US and allied presence in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific. The air-manoeuvre project itself is focused on a single battalion rather than on full-spectrum campaign integration. These constraints matter and should temper alarmist readings. They do not, however, alter the direction of movement. The relationship is transitioning from undirected signaling toward scenario-specific coordination, and from abstract declarations of partnership toward concrete, if still limited, preparations against clearly identifiable adversaries.

Ambiguity is an integral feature of this process. Both capitals preserve uncertainty about thresholds, red lines and the precise conditions under which they would act in support of the other. That uncertainty complicates allied risk calculus. It forces decision makers in Washington, Tokyo and European capitals to consider the possibility that escalatory moves in one theater will elicit opportunistic or solidaristic responses in the other. It raises questions about how far support for Ukraine can be expanded without provoking compensatory Chinese behavior in the Western Pacific, how much pressure can be applied over Taiwan without inviting Russian counter-moves in the Baltics or Arctic, and how far economic coercion can be used against China without accelerating its deepening alignment with Russia.

The policy implications follow directly. For the United States, the core planning assumption can no longer be that a major Taiwan contingency will substitute for an acute crisis in Europe. The more realistic assumption is that a Pacific war would overlay, rather than replace, a still-active war in Ukraine and a tense standoff with Russia along NATO’s borders. This requires force structure decisions, munitions stockpiling, industrial base investments and basing arrangements that are designed for concurrent stress in both theaters. It also requires alliance management strategies that explicitly allocate roles and responsibilities under such conditions.

For European states, the battalion case intensifies ongoing debates about strategic autonomy and burden sharing. If US high-end capabilities are increasingly earmarked for the Indo-Pacific, Europe’s ability to maintain a credible deterrent and defense posture against Russia with predominantly European forces becomes pivotal. This is not primarily a question of aligning with US policy toward China. It is a question of preserving European strategic agency in an environment where US attention and assets are structurally stretched.

For Japan and Taiwan, the integration of Russian capacity into the Western Pacific security equation means that the northern maritime and air approaches can no longer be treated as a separate security problem. Investments in anti-submarine warfare, ballistic missile defense, hardened infrastructure and dispersed basing in northern Japan are now directly relevant to any scenario in which Chinese and Russian forces coordinate to stretch allied responses across the length of the first island chain. Taiwan’s planners, in turn, must consider that a future conflict may involve attritional pressure not only from the south and east but also from activity in the northern vectors that constrain reinforcement and complicate maritime and air movements.

Finally, for those engaged in crisis management and diplomacy, the conclusion is that neither theater can be negotiated in isolation. Any serious attempt to construct guardrails around escalation in Europe must take into account Beijing’s calculus over Taiwan. Any framework aimed at stabilizing the Taiwan Strait must factor in the incentives and capabilities that Russia brings to a wider confrontation with the West. There is no longer a stable analytical or diplomatic boundary separating Euro–Atlantic and Indo-Pacific security.

The airborne battalion that Russia is training for China will not determine by itself the outcome of a future battle over Taiwan. Its importance lies in what it reveals about the emerging geometry of great-power confrontation. The conceptual line that once separated the Euro–Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters as distinct problems is being deliberately eroded from the other side. Western strategy, force planning and diplomacy will have to adjust to a world in which that separation can no longer be assumed.