The United States has become the central provider of advanced conventional arms in the contemporary international system. According to the latest Stockholm International Peace Research Institute data, US exports represented about 43 percent of global transfers of major weapons in the period 2020 to 2024, an increase from 35 percent in 2015 to 2019. A new dataset compiled by Bruegel on all United States Foreign Military Sales notifications from 2008 to September 2025 makes it possible to understand with unusual precision how this dominance is structured across regions, systems and industrial actors.

This article uses that dataset, together with global arms transfer data and recent scholarship on hierarchy, to explore the political consequences of Foreign Military Sales as a tool of alliance management and strategic competition. It advances three claims. First, the geography of Foreign Military Sales has shifted markedly since 2008. The Near East and South Asia were the main destinations in the years before the Arab uprisings. Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and particularly after the full scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Europe has become the single largest Foreign Military Sales region in terms of notified value, while East Asia and the Pacific have experienced a more gradual but sustained rise. Second, the bulk of these notified sales are concentrated in a narrow set of platforms and families of weapons, including F 35 and F 16 aircraft, Patriot air and missile defence, and heavy armour and rocket artillery. This concentration generates deep technological and logistical dependence that locks allied and partner forces into US controlled supply chains, software and doctrine. Third, Foreign Military Sales relationships reproduce a hierarchical order that gives Washington significant coercive leverage, yet also create vulnerabilities. Allies and partners now confront an environment in which US political decisions, industrial constraints and export controls can suddenly shape their own military readiness. At the same time, alternative suppliers, especially France and South Korea, are increasing their reach, which allows some clients to diversify and test US reliability.

The article situates these arguments in the literatures on arms transfers, alliance politics and international hierarchy. It combines descriptive analysis of the Foreign Military Sales dataset with an interpretive discussion of three regional theatres: Europe, the Near East and South Asia, and East Asia and the Pacific. The conclusion draws out implications for US strategy, for European debates about defence autonomy, and for partners in Asia and the Middle East who seek to balance dependence on US technology with growing pressure to align on contested conflicts such as Ukraine and Gaza.

Conventional arms transfers have always had a dual character: they are both commercial contracts and instruments of statecraft. In the case of the United States, that dual character is institutionalised in the Foreign Military Sales programme. Foreign Military Sales is a government to government channel, authorised under the Arms Export Control Act, through which foreign governments purchase defence articles and services from the US government rather than directly from private firms. The Defence Security Cooperation Agency manages this channel and explicitly describes it as an instrument to strengthen US security and to promote what US law labels international peace.

In recent years, Foreign Military Sales has attracted renewed attention for three reasons. The first is empirical. Since 2014 there has been a visible surge in European demand for US equipment, driven by the Russian annexation of Crimea, the full escalation of the war in Ukraine in 2022 and a general reassessment of defence needs within the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the European Union. The second is structural. The relative decline of Russian exports, combined with Chinese caution in exporting high end systems beyond a limited set of clients, has further entrenched the US position as the dominant supplier. SIPRI’s most recent fact sheets show that although the overall global volume of arms transfers has remained roughly stable, US exports increased by about one fifth between 2015 to 2019 and 2020 to 2024.

The third reason is conceptual. Scholars who study international hierarchy, security communities and coercive diplomacy have begun to use arms transfer networks as a way of measuring informal authority and dependence. Work by David Lake on hierarchy, by Kyle Beardsley on the role of arms transfer communities in the provision of order, and by Johnson and Willardson on how aircraft transfers fit within international relations theories, all suggest that weapons sales are not simply adjuncts to alliances but constitutive elements of security orders.

The Bruegel Foreign Military Sales dataset that underpins this article extends those debates. It contains information on all notifications of proposed Foreign Military Sales cases submitted to the US Congress from 2008 to September 2025. For each notification it reports the recipient state, the financial value in both current and constant terms, descriptions of the equipment, where possible the number of major items, and the prime contractors involved. The notifications also describe associated support such as training, spare parts and logistical assistance.

This article uses the dataset to advance a political argument. Foreign Military Sales is not only a record of who buys what from the United States. It is a map of how US power is embedded in the everyday operation of allied and partner militaries. By tracing the geography, composition and industrial concentration of Foreign Military Sales since 2008, we can see the contours of a security hierarchy that is more finely grained than the formal alliance system.

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. The next section situates Foreign Military Sales within the broader global arms economy and highlights the distinctive features of the programme compared to other channels such as Direct Commercial Sales and Foreign Military Financing. A third section describes the dataset and the analytical strategy. A fourth section examines global trends in Foreign Military Sales notifications, followed by three regional case discussions. A final section draws out the implications for hierarchy and policy.

Foreign Military Sales in the global arms economy

The United States uses several institutional channels to move weapons and associated services abroad. Foreign Military Sales is the central one. It is formally a government programme. Recipient states sign a Letter of Request that expresses interest in acquiring specific capabilities. The US executive branch evaluates the request, consults with Congress where required and drafts a Letter of Offer and Acceptance that sets out the terms and price. Notification to Congress is mandatory above threshold values that depend on whether the recipient is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, a major non NATO ally, or another state. The Defence Security Cooperation Agency collects and publishes these notifications, which form the basis of the Bruegel dataset.

Other US export instruments are important but structurally different. Direct Commercial Sales authorisations are the main channel for exports that foreign governments purchase directly from US firms under individual export licences. These licences can cover an entire category of equipment for several years, and many authorisations do not lead to completed deliveries. Foreign Military Financing and related budgetary instruments are not sales but grants or loans that allow recipients to purchase equipment, often via the Foreign Military Sales channel.

At the level of the global arms economy, these channels, together with programmes such as Excess Defense Articles and ad hoc assistance schemes, have underpinned the sustained US share of major arms exports. The 2025 SIPRI Yearbook chapter on international arms transfers notes that US exports grew by about 21 percent between 2015 to 2019 and 2020 to 2024, and that the United States is likely to remain without serious rival as an exporter for the foreseeable future, in part because of large order backlogs for aircraft and missile defence systems.

The distinction between Foreign Military Sales and other channels matters for two reasons. First, Foreign Military Sales gives the US government a direct managerial role in the acquisition process. It handles procurement from the prime contractor, integrates training and support, and remains the contractual counterpart. Second, because Foreign Military Sales notifications are more standardised than many Direct Commercial Sales documents, they provide much richer information for systematic analysis of volumes, equipment types and industrial actors.

The analysis that follows relies primarily on the Bruegel Foreign Military Sales dataset that compiles all public notifications issued by the Defence Security Cooperation Agency between January 2008 and mid September 2025. For each notification the dataset records the reported value in US dollars, both in current terms and in constant 2024 terms, a short textual description of the sale and a classification by recipient region and equipment type. In many cases, it also includes the number of major platforms or weapon units, the name and location of prime contractors, and references to associated services such as training, maintenance and logistics.

The notifications are proposals, not guaranteed deliveries. Some proposed deals are cancelled, amended or delayed. In addition, Foreign Military Sales covers only part of the broader universe of US arms transfers. Direct Commercial Sales, drawdowns from US stocks under Ukraine Security Assistance and Israel related authorities, and certain special programmes are not fully captured. Yet comparison with the Department of Defense Historical Sales Book suggests that total implemented Foreign Military Sales cases track the aggregate value of notifications closely over time.

The dataset allows several types of analysis. In this article the focus is on three questions.

The first question concerns global trends. How have aggregate notified values and the number of cases evolved from 2008 to 2025 and how does this line up with key geopolitical events such as the global financial crisis, the Arab uprisings, Russia’s two phases of aggression against Ukraine and the intensification of tensions in the Indo Pacific.

The second question relates to geography. Which regions and individual countries account for the bulk of notified sales and how has this changed over time. Particular attention is paid to Europe, which has moved from a relatively modest Foreign Military Sales customer to the leading region in the aftermath of the 2022 invasion of Ukraine; to the Near East and South Asia, historically the largest buyers of US equipment; and to East Asia and the Pacific, where concerns about China and North Korea shape demand.

The third question is about the composition of dependence. Which platforms and categories of equipment dominate notified sales, and what does this imply for the depth of technological and logistical dependence. Here the analysis draws on more detailed coding within the Bruegel project and links it to qualitative case material on particular systems, such as F 35 aircraft, Patriot air and missile defence batteries, and High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems.

The analytical strategy is descriptive rather than econometric. The aim is to connect observed patterns in the Foreign Military Sales data to theoretical claims about hierarchy and alliance politics. Quantitative figures are interpreted in light of qualitative evidence on industrial capacity, political debates and crisis episodes.

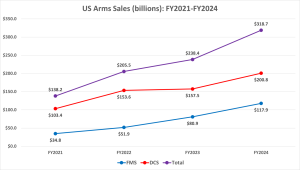

In constant 2024 dollars, aggregate Foreign Military Sales notifications from 2008 to 2024 show a general upward trend with several marked surges. There is a first peak around 2010 and 2011, associated largely with large packages for Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies. These included mixed bundles of fighter aircraft, attack helicopters, missile defence and extensive support. There is a second notable increase around 2017 to 2018, with high value packages for both Near Eastern and Asian customers. The most striking feature, however, is the acceleration after 2020.

By 2020 total notified Foreign Military Sales values roughly doubled compared to the long term annual average that prevailed in the decade after 2008. The number of separate notifications also increases in the early 2020s, suggesting not only larger individual packages but also a broader spread of deals across partners. In 2024 the number of publicly notified Foreign Military Sales cases reached a record, and preliminary data for the first three quarters of 2025 suggest that high volumes are continuing, even as actual deliveries lag because of industrial constraints in munitions and certain specialised components.

These aggregate patterns align closely with global trends in arms transfers. SIPRI’s update on the Arms Transfers Database indicates that global transfers of major weapons remained nearly flat in volume between 2015 to 2019 and 2020 to 2024. Yet within that apparent stability there was a substantial shift in destination. Imports to European states increased by an estimated 155 percent between the two periods, while imports by many regions in the global South decreased. The Foreign Military Sales dataset reveals that much of this European surge has been channelled through US suppliers.

At the same time, there is a visible decline in notifications associated with certain traditional buyers, particularly in the Near East, which is partly explained by saturation effects and partly by political friction over the use of US supplied weapons in Yemen and Gaza. Recent restrictions or suspensions of arms transfers to Israel by some European states illustrate how contested such relationships have become, even though the vast majority of Israel’s major conventional weapons continue to come from the United States and Germany.

The European case is where the transformation in Foreign Military Sales is easiest to see. Before 2014, European NATO members and associated states bought significant quantities of US equipment, but purchases were often incremental: upgrades of legacy aircraft, air to air and air defence missiles, and certain command and control systems. The coalition operations in the Balkans and Afghanistan highlighted persistent gaps in European capabilities, yet defence budgets stayed low and political incentives to commit to major new platforms were weak.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 altered this picture. European governments began to reinvest in defence, but the change was gradual until 2022. The full scale invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing war triggered a more abrupt shift. Germany’s announcement of a Zeitenwende in defence policy, Poland’s large scale modernisation plans, and similar revisions in Finland, Sweden, the Baltic states and several Southern European states translated into orders.

The Foreign Military Sales notifications show that Europe has now overtaken the Near East in yearly notified values. The central pillars of this new dependence are three families of systems. The first is the F 35 aircraft. Notifications for F 35 sales to Belgium, Finland, Germany, Poland, Switzerland, Greece and the Czech Republic add to the earlier orders from programme partners such as Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway. Each of these notifications includes not only the aircraft but also extensive packages of precision guided munitions, engines, simulators, maintenance equipment and software support.

The second pillar is air and missile defence. Patriot systems have been notified for Poland, Romania, Sweden and Spain, among others. These systems involve sophisticated radars, command posts and interceptors that are tightly integrated into US standard networks. Additional air defence systems supplied to European partners, such as NASAMS and Aegis Ashore, deepen that integration.

The third pillar is heavy land systems and rocket artillery. Poland has requested hundreds of Abrams tanks and a large number of High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems. Other eastern flank states have sought US guided artillery ammunition and rocket systems to complement or replace Soviet legacy equipment that they have donated to Ukraine.

This combination of platforms raises a central question for European debates on strategic autonomy. On one side, Foreign Military Sales purchases clearly improve the near term ability of European forces to deter and, if necessary, fight a high intensity war. Interoperability with US forces is enhanced, and the symbolism of joining the F 35 user community is politically significant. On the other side, such purchases lock European states into long term dependence on US software updates, spare parts, munitions resupply and future upgrade decisions. The more Europe invests in these US controlled systems, the more it risks that its future operational freedom will be constrained by US political and industrial choices.

The Near East and parts of South Asia have long been central theatres of US arms export policy. The Foreign Military Sales dataset confirms that in the decade after 2008, Gulf monarchies and their neighbours accounted for the majority of notified values. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait and Egypt requested large packages that combined combat aircraft, attack helicopters, integrated air defence and substantial munitions and support. Israel received Foreign Military Sales support tailored to maintain its qualitative military edge, including advanced aircraft, munitions and missile defence.

The pattern in this region is highly transactional. Arms transfers are intertwined with energy relations, basing agreements, intelligence cooperation and diplomatic initiatives such as the Abraham Accords. Episodes of conditionality reveal how Washington uses Foreign Military Sales as leverage. Examples include the temporary suspension of certain munitions deliveries to Saudi Arabia over concerns about civilian casualties in Yemen, the delay in F 16 deliveries to Egypt following the 2013 coup, and more recent debates about whether to restrict transfers to Israel because of civilian harm in Gaza.

At the same time, Gulf clients and others have used the existence of alternative suppliers to improve their bargaining position. France, the United Kingdom and, more recently, South Korea and Turkey have become visible competitors in segments such as combat aircraft, naval vessels and air defence. Nonetheless, for the most advanced integrated systems, the United States remains unrivalled. This gives Washington a privileged position, but also creates reputational risks. When US supplied weapons are implicated in controversial campaigns, the legitimacy of the broader security relationship comes under pressure among publics and parliaments in Western states.

In East Asia and the Pacific, Foreign Military Sales interacts with a distinct security landscape shaped by concerns about China’s military rise, North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes, and territorial disputes in the South and East China Seas. Japan, South Korea and Australia are the major industrial powers and core US allies in the region. Taiwan, the Philippines and several Southeast Asian states are important, though more vulnerable, partners.

The dataset shows steady Foreign Military Sales activity across the period rather than the dramatic step change seen in Europe after 2022. Japan and South Korea have received successive tranches of F 35 aircraft, upgrades for older F 15 and F 16 fleets, Aegis combat systems for surface combatants, and integrated air and missile defence capabilities. Australia has combined Foreign Military Sales purchases of aircraft and missiles with separate arrangements for submarines under the AUKUS framework, which lie outside standard Foreign Military Sales reporting.

For Taiwan and certain Southeast Asian states the pattern is more episodic. Notifications for air defence, coastal defence cruise missiles, surveillance radars and command and control systems are often controversial in Beijing, which regards them as violations of understandings on the status of Taiwan and as encirclement efforts in Southeast Asia. From Washington’s perspective, such transfers are part of a strategy of denial intended to raise the cost of aggression rather than guarantee dominance. The direction of these transfers therefore expresses a strong alignment with US strategic priorities, yet the volume and speed of deliveries are constrained by both political and industrial factors.

A distinctive feature of East Asia is the growing production capacity of US allies themselves. South Korea has emerged as a mid tier exporter of armoured vehicles, artillery and aircraft, winning contracts in Eastern Europe and the Gulf. Japan is cautiously loosening restrictions on defence exports and exploring joint development projects. These trends mean that while the United States continues to supply the most sophisticated elements of the regional military balance, its allies are less dependent for mid range systems than traditional Near Eastern clients.

The empirical patterns described above can be interpreted through the lens of hierarchy in international relations. In Lake’s account, a hierarchical relationship exists when a dominant state provides security or other public goods and, in return, subordinate states accept constraints on their autonomy. Arms transfers are one of the mechanisms through which such constraints become material. When a patron state designs, manufactures and supplies core military platforms, it gains power over the subordinate’s ability to generate force.

Foreign Military Sales contracts codify this power in several ways. End use and re transfer conditions give the United States legal grounds to shape how recipients can use the equipment and to which third parties they may pass it on. Export control rules restrict access to sensitive software, encrypted communications and certain types of ammunition. Regular upgrades are necessary to maintain operational performance in the face of evolving threats, which ensures that the client must repeatedly seek US approval and funding for modernisation.

These elements provide what might be called potential coercive leverage. In principle, Washington can threaten to delay deliveries, suspend upgrades or deny munitions as a way to influence recipient behaviour. Historical examples show that these threats are sometimes carried out. Yet the effectiveness and credibility of such leverage vary.

In Europe, where the United States and its allies share a dense web of institutional commitments, the primary effect of Foreign Military Sales may be reassurance rather than coercion. European states rely on US equipment because they expect the alliance to endure and because industrial alternatives are, in the short term, limited. If US domestic politics made the alliance less reliable, the very depth of Foreign Military Sales based dependence would become a source of anxiety and might accelerate efforts to create autonomous European capabilities.

In the Near East, where relationships are more transactional and regime survival often a prime concern, the threat of interruption in the flow of spare parts and munitions has more immediate bite. At the same time, the availability of alternative suppliers such as Russia, China, France and South Korea reduces the long term effectiveness of such threats. There is a risk that overuse of conditionality simply encourages clients to diversify away from US controlled systems where they can.

In East Asia, Foreign Military Sales plays a more subtle role. It binds regional allies into a technical and doctrinal ecosystem that enhances interoperability and signals commitment. At the same time, the United States must reconcile its desire to arm partners for deterrence with its reluctance to fuel an arms race or to transfer capabilities that could embolden partners to take unilateral risks, for instance in the Taiwan Strait. The balance between empowering and restraining partners is particularly delicate in this theatre.

From a policy perspective, the Foreign Military Sales record since 2008 suggests several lessons, both for the United States and for client states.

For Washington, the first imperative is to recognise that Foreign Military Sales is no longer a peripheral activity. It is a central pillar of alliance management. Decisions about the sequencing of deliveries, prioritisation between ongoing war efforts such as Ukraine and Israel, and allocation of scarce munitions and air defence interceptors affect not only battlefield outcomes but also perceptions of reliability. Recent media coverage of delays in providing certain munitions to Ukraine or debates over restrictions on transfers to Israel illustrates how allocation choices are scrutinised in real time by allies and publics.

A second implication is that US policymakers should treat conditionality in arms supplies as a blunt tool. There are good normative reasons to tie arms exports to respect for humanitarian law and to concerns about regional escalation. Yet the more openly Washington uses the threat of interrupting transfers, the greater the incentive for clients to hedge with alternative suppliers. In some cases, political conditionality may be better pursued through other channels, such as sanctions on individual officials or targeted restrictions on specific munitions, rather than broad suspensions of entire platform lines.

A third implication concerns industrial capacity. The sudden increase in Foreign Military Sales notifications, combined with urgent assistance to Ukraine and ongoing commitments in Asia, has exposed limits in the US defence industrial base, particularly in the production of guided artillery ammunition, air defence interceptors and certain missiles. Addressing these bottlenecks requires not only larger orders but also more predictable demand signals and, in some cases, co production or licensed production arrangements with trusted partners. The Historical Sales Book and updated Foreign Military Sales activity demonstrate that demand will remain high into the late 2020s, which justifies investments in new production lines.

For European allies, the Foreign Military Sales data are a mirror that reveals how far strategic autonomy lies from present reality. In air power and missile defence, European states are deeply dependent on US equipment. European multinational projects such as the Future Combat Air System and the Global Combat Air Programme, as well as joint missile defence initiatives, aim to reduce this dependence, but they will take many years to deliver operational capabilities. In the meantime, European governments face a delicate task: they must consolidate their contributions to NATO deterrence, which points toward continued purchases of US platforms, while also fostering a European industrial base that is robust enough to provide alternatives in the longer term.

For partners in the Near East and Asia, the dataset underscores that balanced portfolios are prudent. The United States will remain the primary source of high end aircraft and integrated air defence, but clients can reduce vulnerability by cultivating additional suppliers for armoured vehicles, artillery, communications equipment and certain missile systems. South Korea’s success in marketing artillery and armoured platforms to European and Middle Eastern customers, and Turkey’s growing exports of drones and air defence, show that such diversification is feasible.

Finally, for international efforts to regulate the arms trade, the Foreign Military Sales data confirm a familiar tension. Transparency and public reporting, such as the Defence Security Cooperation Agency notifications and the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, improve accountability. They allow scholars and civil society to scrutinise who is selling what to whom. At the same time, the most politically sensitive decisions are often taken in classified settings, and the criteria that guide those decisions remain ambiguous. This gap between formal transparency and substantive accountability is likely to widen as arms exports become more central to geopolitical competition.

Foreign Military Sales is often discussed in narrow bureaucratic or commercial terms, as a process for moving equipment from US factories to foreign end users. The evidence examined here suggests a different reading. Since 2008, and especially since the mid 2010s, Foreign Military Sales has become one of the main ways in which the United States organises its security relationships. It creates webs of dependence that are material, institutional and political.

The geography and composition of those webs have shifted. The Near East and South Asia remain important clients, but Europe has become the principal driver of new notifications in response to Russian aggression. East Asia and the Pacific have seen sustained, if less dramatic, growth in orders as regional states adapt to China’s rise and North Korea’s capabilities. Across these regions, a small number of platform families account for a large share of notified values, binding recipients into long term relationships with US industry and policy.

For international relations scholarship, the new Foreign Military Sales dataset opens promising research paths. One path is to integrate it with network models that capture the structure of arms transfer communities and examine how those communities influence conflict onset and alliance behaviour, as Beardsley and others have begun to do. Another is to combine it with domestic political variables in recipient states to explore how regime type, civil military relations and public opinion affect both demand for US arms and reactions to conditionality.

For practitioners, the central message is that arms transfers must be treated as a core element of strategy, not as a technical afterthought. The United States has leveraged its industrial and technological advantages to anchor a far reaching security hierarchy. That hierarchy will only remain stable if clients trust that the flow of equipment, upgrades and munitions will not become arbitrary instruments of domestic political contestation in Washington. Conversely, clients must confront the reality that dependence on US systems brings both security benefits and constraints on autonomy.

Managing these tensions will be a defining task in the 2020s. Foreign Military Sales is a central arena where the balance between reassurance and coercion, between hierarchy and autonomy, and between industrial capacity and strategic ambition, is negotiated in concrete terms.